In 2022, after some Covid-19 and visa related delays, I finally arrive at IIT Delhi to begin my PhD fieldwork, and India proved to be an excellent place to research the causes of women’s empowerment…

“The Indian case study is theoretically most instructive for two reasons: on the one hand, since India is one of those few polities where tradition and modernity exist side-by-side, understanding of the feminist issues reveals how the Western-driven conceptualisation is inadequate in this respect… A study of feminism with reference to specific aspects of struggle for gender equality and women empowerment also reveals, on the other hand, the peculiar nature of the struggle, which is not always about specific feminist issues, but linked with the wider struggle for equality and freedom.”

– Bidyut Chakrabarty

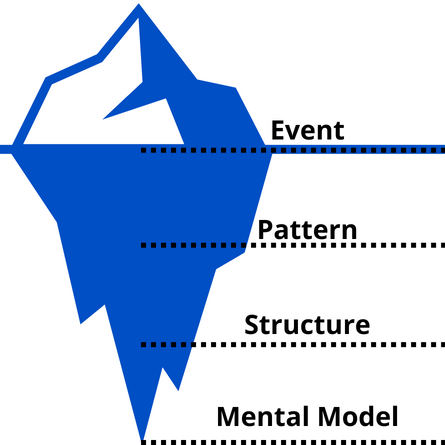

If any emergent properties are to be attributed to empowerment as a result of its components and relations, we must be able to separate the causal structures—entities, with their properties and generative mechanisms—from the effects it creates. In order to differentiate the causal structure of empowerment from the patterns of events it creates, these patterns of events would first need to be identified. To identify these patterns, I began first by collecting stories about women’s individual experiences of empowerment, and each story that was shared during my fieldwork was sorted and preliminarily analysed using a common systems-thinking tool, the iceberg model.

There are four levels to the model, beginning with the top ‘events’ level. This is where any events or experiences described by participants in the empirical domain would be placed. ‘Events’ in the critical realist terms must be located at a particular time and space (not an ongoing process) and involve some kind of change to a system or situation—if there’s no change, there’s no event. One story shared by a participant was that as a Dalit woman she fears that she will face stigma if she goes out in her wider community—once, a water bottle was thrown out by a vendor because she touched it. The story of the water bottle incident is itself an event, but this single story can also provide additional data for the deeper levels of the iceberg.

Next is the ‘patterns and trends’ level, where temporality is introduced with abductive reasoning; where the information and any observations from the discussion are grouped together with similar events to notice any key themes. A trend that came up in the interviews was that other Dalit women shared this sentiment—a fear that they would face stigma in their wider community, with women agreeing that they don’t like to go into the nearby town alone, or they don’t like to go out after dark, and if they were more empowered, they would feel safe doing so; the single event (the water bottle incident) helps to discover a pattern or trend.

Next, we move from identifying ‘events’ to ‘things’ in the iceberg model, with the underlying structures level— the “arrangement of social relationships” that make up a social system at both the micro and macro levels. This would encompass the organised, usual, or standard ways by which a society meets its basic needs, relating to areas such as the family, religion, law, politics, economics, education, science, medicine, the military, and the mass media. The story of the water bottle, and the conversation amongst the women that ensued afterwards, highlighted underlying structures in their communities; these women feel safe, respected and empowered in their families and local village, but it is still commonplace for Dalit women in this community to face overt discrimination and stigma beyond their home. The caste system is still an underlying structure that influences the way these communities are organised.

Finally, there is the ‘mental models’ level of the iceberg, which is made up of the cultural aspects of the system. Understanding any underlying mental models is important because ideas and rhetoric can themselves have causal power. The stories that were shared often provided insights into how women conceptualise empowerment, and while there may indeed be similarities in how empowerment was conceptualised across similar contexts, it shouldn’t be assume that there is ever a “one-size-fits-all” definition of any concept, otherwise important distinctions and nuances may be missed. From the water bottle story shared by this woman, it gives an insight into how she conceptualises empowerment— as an absence of fear, where feeling safe would provide her the freedom to be herself in her wider community.

The story of the water-bottle was just one of many stories that was influential in helping me develop a framework for empowerment that would draw upon the individual experiences of women, while distinguishing between context (patterns and trends) and causal structures (entities and mechanisms).